THANK YOU FOR VISITING SWEATSCIENCE.COM!

My new Sweat Science columns are being published at www.outsideonline.com/sweatscience. Also check out my new book, THE EXPLORER'S GENE: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map, published in March 2025.

- Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience)

***

Another month, another neat paper from Paul Williams’ prolific National Runners’ Health Study, online at Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. With his sample of >100,000 runners, Williams took two well-established correlations — those who eat more meat tend to weigh more, as do those who eat less fruit — and checked to see whether these links between diet and weight were affected by how much exercise the subjects did.

The first thing to emphasize: don’t get hung up on whether or why meat and fruits are “good” or “bad.” That’s not what this study is about. It’s just a cross-sectional study, so individual dietary markers (like meat and fruit consumption) may simply be markers of other behaviours. But whatever the reason for these correlations, they’re well established. The question is: if you do lots of exercise, are you less likely to get fat from whatever dietary patterns are associated with high meat and low fruit intake?

The answer is yes:

Specifically, compared to running < 2 km/d, running >8 km/d reduced the apparent BMI increase per serving of meat by 43% in men and 55% in women, and reduced the apparent BMI reduction per serving of fruit by 86% in men and 94% in women.

Williams suggests two possible explanations for this effect:

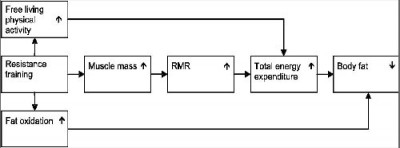

- Aerobic exercise trains your body to burn a higher percentage of fat rather than carbohydrate for fuel. In contrast, people who burn a lower percentage of fat compared to carbohydrate are thought to be at higher risk of gaining weight.

- Exercise improves “coupling between energy intake and expenditure.” In effect, researchers have found that people who exercise more tend to develop stronger appetite cues that tell them when they’re hungry or full. There have been some neat studies of this, where subjects were fed “disguised” drinks that had either high or low energy content. As a later meal, regular exercisers unconsciously adjusted by eating more or less (depending on which drink they’d received) compared to sedentary people.

So why is this important? It goes back to the never-ending “diet versus exercise” debate for weight loss, a false dichotomy if there ever was one. Williams notes that a recent review of epidemiological studies looking for links between reported levels of physical activity and prospective weight gain concluded that they “generally failed” to show any links. This contrasts sharply with Williams’ own findings, which clearly show that “running attenuates age-related weight gain prospectively in proportion to the exercise dose, and that increasing and decreasing exercise produces reciprocal changes in body weight.” He speculates that the difference arises because running is relatively vigorous. It’s also easy to quantify compared to vague epidemiological studies that have subjects estimate how much time they spend playing soccer or mowing the lawn, at what subjective level of effort.

Whatever the mechanism, it’s a good reminder that exercise can play a role in weight control. It certainly doesn’t give you a free pass on your diet — but if you do enough, it seems to give you a little more wiggle room.