THANK YOU FOR VISITING SWEATSCIENCE.COM!

My new Sweat Science columns are being published at www.outsideonline.com/sweatscience. Also check out my new book, THE EXPLORER'S GENE: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map, published in March 2025.

- Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience)

***

It’s widely known that the old “220 minus your age” equation isn’t very good at determining your maximum heart rate. So what’s better? A new study from the University of Hawaii, recently published online at the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, tested nine different prediction equations, along with a surprisingly accurate way of determining your true max heart rate in about 30 seconds (sort of).

The study looked at 96 volunteers with an average age of about 22. That’s the first caveat: these results are only relevant for people in that general age group. And the volunteers were phys ed students, which means they’re likely to be more physically active than the general population.

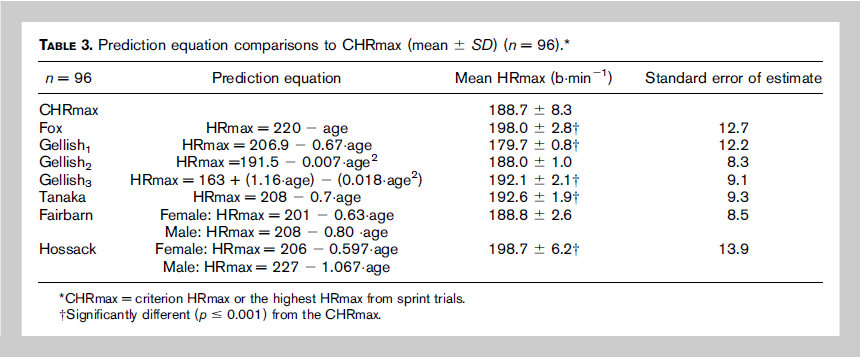

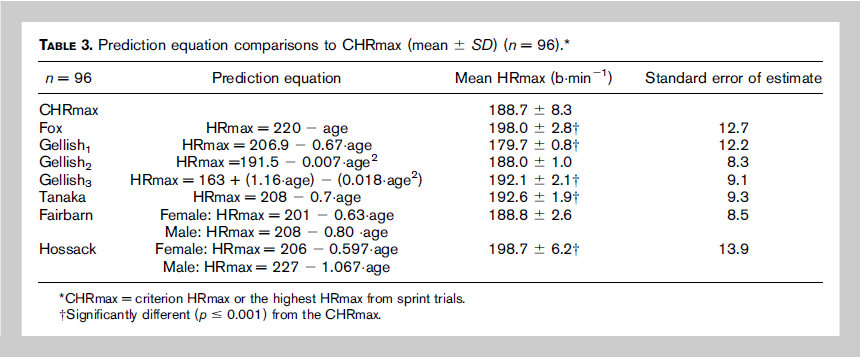

I’ll start with the less interesting part of the study. Here’s the data from the equations they tested for all 96 subjects:

“CHRmax” is basically the “real” max heart rate. So they conclude that Gellish2 (191.5 – 0.007*age^2) and Fairbarn (201 – 0.63*age for women, 208 – 0.80*age for men) are the most accurate for this population. Maybe so — although trying to fit a function of age to data taken from subjects who are all virtually the same age seems a little weak to me. But the bigger problem is something they themselves note in their introduction:

The most commonly used Fox equation [i.e. 220 minus age] has been reported to have an SD [standard deviation] between 10 and 12 b/min. Thus, when estimating HRmax using the Fox equation, approximately 66% of the population should fall within +/-10 beats of the actual HRmax, but for the remaining population, the actual HRmax could differ by as much as 12–20 b/min or more.

I don’t know why they’re saying this is a property of the Fox equation. This is a fundamental property of human physiology: heart rate varies between individuals, so ANY equation based only on age will be more than 10 beats off for at least a third of the population. So for practical exercise prescription purposes, who cares which equation is more accurate?

Much more interesting is the way they calculate HRmax. They did the usual graded treadmill test to exhaustion to determine “true” max for 25 of their volunteers. Then they tested two other protocols. One was the Wingate test, which is basically 30 seconds all-out on an exercise bike. It was a crappy predictor, more than 10 beats below the actual average.

The second test was really simple: they had the subjects sprint as hard as they could for 200 metres on a standard track, with a running start. That’s it. And they measured their heart rate during the sprint. The average from the treadmill test was 190.0; the average determined from the 200m sprint (which takes a little over 30 seconds for most people) was 190.1. Pretty darn good.

Now, there are some caveats. The fact that the averages were close doesn’t mean everyone got identical values on the two tests. In fact, the “mean absolute error” was 5.8 bpm — but since the treadmill test was higher about half the time and the sprint was higher the other half, the averages balanced out.

Also, they didn’t do just one 200 sprint. They actually did two, but separated by at least three days. Each individual sprint, on average, underestimated the HRmax. The first sprint produced an average of 187.9; the second sprint produced an average of 186.3. So this test wasn’t as reliable at getting right up to HRmax. But when they gave people two tries, most people seem to have nailed at least one of the tries. Presumably if you gave them five tries (spread over several weeks), you’d get an even higher average max value. Of course, the same is true of the treadmill test: not everyone will execute it perfectly, so if you do it twice, the average value will probably creep up a bit. But what this study tells us is that, for this group of subjects (and remember, these are young phys ed students who are capable of sprinting 200 metres all out without pulling up lame halfway), give them two cracks at sprinting 200 metres and then take the highest heart rate they produce, and you’ll have a very good estimate of maxHR. It’s a heck of a lot cheaper and quicker than a graded exercise test — and a billion times more useful than any equation based only on your age.

The trend is pretty clear. The age by which 50% of the population died was 73.5 for the general cohort, and 81.5 for the Tour de France riders — who, according to the paper, ride about 30,000 to 35,000 km per year (though I’d be surprised in the riders competing in the 1930s were training as hard as modern riders).

The trend is pretty clear. The age by which 50% of the population died was 73.5 for the general cohort, and 81.5 for the Tour de France riders — who, according to the paper, ride about 30,000 to 35,000 km per year (though I’d be surprised in the riders competing in the 1930s were training as hard as modern riders).