THANK YOU FOR VISITING SWEATSCIENCE.COM!

My new Sweat Science columns are being published at www.outsideonline.com/sweatscience. Also check out my new book, THE EXPLORER'S GENE: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map, published in March 2025.

- Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience)

***

Here’s a graph, from a recent paper on nutrition during long (marathon and longer) endurance competitions, that’s worth a close look:

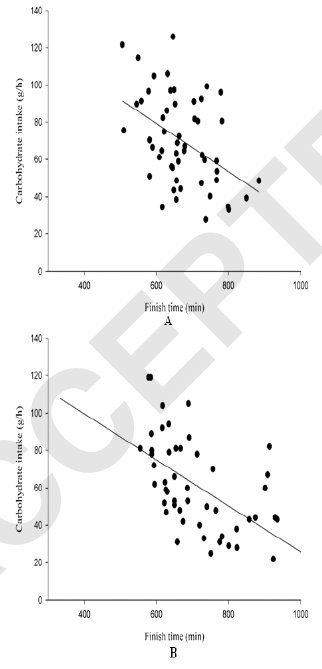

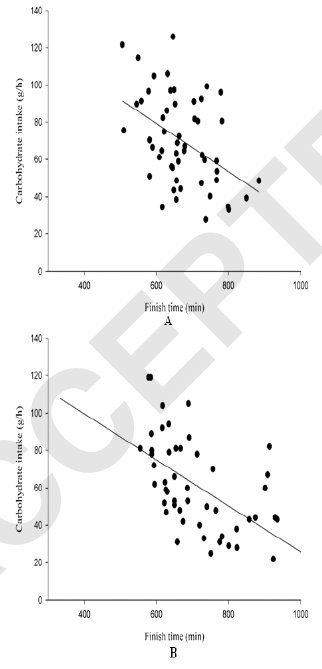

What do you see? A bunch of dots scattered randomly? Look a bit more closely. The data shows total carb intake (in grams per hour) by racers in Ironman Hawaii (top) and Ironman Germany (bottom), plotted against finishing time. It comes from a Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise paper by Asker Jeukendrup’s group (with several collaborators, including Canadian Sport Centre physiologist Trent Stellingwerff) that looked at “in the field” nutritional intake and gastrointestinal problems in marathons, Ironman and half-Ironman triathlons, and long cycling races. The basic conclusion:

What do you see? A bunch of dots scattered randomly? Look a bit more closely. The data shows total carb intake (in grams per hour) by racers in Ironman Hawaii (top) and Ironman Germany (bottom), plotted against finishing time. It comes from a Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise paper by Asker Jeukendrup’s group (with several collaborators, including Canadian Sport Centre physiologist Trent Stellingwerff) that looked at “in the field” nutritional intake and gastrointestinal problems in marathons, Ironman and half-Ironman triathlons, and long cycling races. The basic conclusion:

High CHO [carbohydrate] intake during exercise was related to increased scores for nausea and flatulence, but also to better performance during IM races.

So basically, taking lots of carbs may upset your stomach, but helps you perform better. It’s important to remember that gastrointestinal tolerance is trainable, so it’s worth putting up with some discomfort to gradually raise the threshold of what you’re able to tolerate.

Anyway, back to that graph: while it may look pretty random, statistical analysis shows a crystal-clear link between higher carb intake rates and faster race times, albeit with significant individual variation. Obviously there are some important caveats — it may be, for example, that faster athletes tend to be more knowledgeable about the benefits of carbs, and thus take more. Still, it’s real world data that tells us the people at the front of the race tend to have a higher carb intake rate.

One other point worth noting. The traditional thinking was that humans generally couldn’t process more than 60 grams of carb per hour. Over the last few years, thanks to multiple-carb blends, that threshold has been pushed up to 90 grams of carb per hour. In this data set, about 50% of the triathletes were taking 90 g/hr or more.

[UPDATE 10/26: Given all the comments below about the variability in the data, I think it’s worth emphasizing what should be a fairly obvious point. The only way this data would come out as a nice straight line is if Ironman finishing time depended ONLY on carb intake, and was totally independent of training, experience, talent, gender, body size, and innumerable other factors. This is obviously not the case, so we should expect the data to be very broadly scattered. What the statistical analysis shows is that, with p<0.001, faster finishers tended to have consumed carbs at a higher rate. There are many ways to interpret this data; one possibility is that, if your carb consumption is below average, you might wish to try a higher rate of consumption (e.g. 90 g/hr) to see if it helps.]

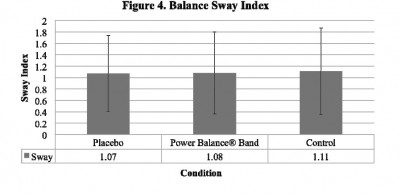

And for all those who still swear that, when the salesman put the bracelet on their wrist, they really did do better on the balance test, it’s worth noting the University of Wisconsin pilot study (cited in the Texas paper) that found that in balance and flexibility tests like the ones used by Power Balance salespeople, you always do better the second time you try it, due to learning effects. So if you try the test first with the bracelet on, then with the bracelet off, you’ll “prove” that the energy flow actually harms your balance. (Or maybe that just means you had the bracelet on backwards…)

And for all those who still swear that, when the salesman put the bracelet on their wrist, they really did do better on the balance test, it’s worth noting the University of Wisconsin pilot study (cited in the Texas paper) that found that in balance and flexibility tests like the ones used by Power Balance salespeople, you always do better the second time you try it, due to learning effects. So if you try the test first with the bracelet on, then with the bracelet off, you’ll “prove” that the energy flow actually harms your balance. (Or maybe that just means you had the bracelet on backwards…)

What do you see? A bunch of dots scattered randomly? Look a bit more closely. The data shows total carb intake (in grams per hour) by racers in Ironman Hawaii (top) and Ironman Germany (bottom), plotted against finishing time. It comes from

What do you see? A bunch of dots scattered randomly? Look a bit more closely. The data shows total carb intake (in grams per hour) by racers in Ironman Hawaii (top) and Ironman Germany (bottom), plotted against finishing time. It comes from